Our fertile attention: from Taoism to terrorism

Cultivating mindful focus in the age of digital conflict

Six pack in hand, I rang the doorbell of my friend’s music studio. He had just posted his new music video to YouTube earlier that day, and I dropped by to celebrate. I would hang out at his studio regularly, and we’d leisurely talk culture, digital strategy, and music. This evening was a little less carefree. We brainstormed about ways to drive more traffic to the video. Intermittently, we’d hit the F5 button to refresh the browser to see if what we were doing was having any effect yet.

Every time we hit refresh, the music video had new comments. It was great to see his fans were showing up and engaging. I’m sure he was glad about that too. His attention, however, was directed elsewhere. Some people didn’t like the song and voiced it in the comment section. Instead of focusing on the supportive messages, he replied almost exclusively to the negative ones. As hard as I tried to get him to focus on embracing his fans, who actually deserved his attention, I could not compete with the emotional draw that getting into an argument with strangers had.

(I should note here that this was years before engaging with YouTube comments would influence their ranking on the page.)

We left for dinner as late as we could before restaurants closed. He had spent much of his attention on the trolls and was in a bad mood. Who wouldn’t be? While he had devoted much of his life to producing music on computers, much of mine was spent on internet forums, IRC chats, and other online pseudonymous communities. I had internalised the internet adage well: Don’t feed the trolls.

Don’t feed the trolls

Over the years, the ability to ignore trolls has become one of my guiding principles for who I choose to work with. Focusing on the negative can be satisfying in the moment, but will put you in a sour and unproductive mood. Energy spent arguing with strangers usually has low returns when compared to building with the people who do believe in what you’re doing. Unfortunately, the online landscape is structured to favour conflict, as recommendation algorithms often identify controversial content as highly engaging and thus push it to more people. There’s even a term for playing into this dynamic: rage-baiting.

Despite knowing better, I, too, fall into this trap on sites like Reddit (I actually recently deleted the account I’d had since 2007). Changing my behaviour through pure discipline, for me, rarely really works. I need to understand the behaviour, the triggers, and how that interacts with my impulsivity. I find that increasing my understanding makes it much easier to change a behaviour. Change then becomes almost effortless, which often feels unfair compared to the amount of near-impactless effort I spent before.

One book that helped me develop a healthier relationship with the internet is Tim Wu’s The Attention Merchants, which talks about the history of media’s harvesting of attention. I recommend this book regularly, and this will not be the last time you’ll see it mentioned here. In his book, Wu references philosopher and “father of American psychology” William James (emphasis mine):

“As William James observed, we must reflect that, when we reach the end of our days, our life experience will equal what we have paid attention to, whether by choice or default. We are at risk, without quite fully realizing it, of living lives that are less our own than we imagine.”

I doubt he could have imagined the extent to which our attention is directed into a constant state of distractedness now. William James died of heart failure in 1910. That’s a decade before widespread radio ownership.

Everyone will have some books, documentaries, or other inspiration sources that have helped shape their beliefs to this day. My early twenties’ mental framework was characterised by Zen Buddhist philosophy, McLuhanism, a curiosity for concepts from Jungian psychology, and Adam Curtis’ The Century of the Self documentary. And let’s be honest, the occasional psychedelic experience through the then-legally available psilocybin mushrooms.

What also stuck with me from those days is this quote by Lao Tzu, the legendary founder of Taoism:

“Watch your thoughts, they become your words; watch your words, they become your actions; watch your actions, they become your habits; watch your habits, they become your character; watch your character, it becomes your destiny.”

It is this combination of Adam Curtis, McLuhan and Tim Wu’s understanding of media and the ‘attention economy’ with Lao Tzu’s words, that guides how I try to navigate the world — online, included.

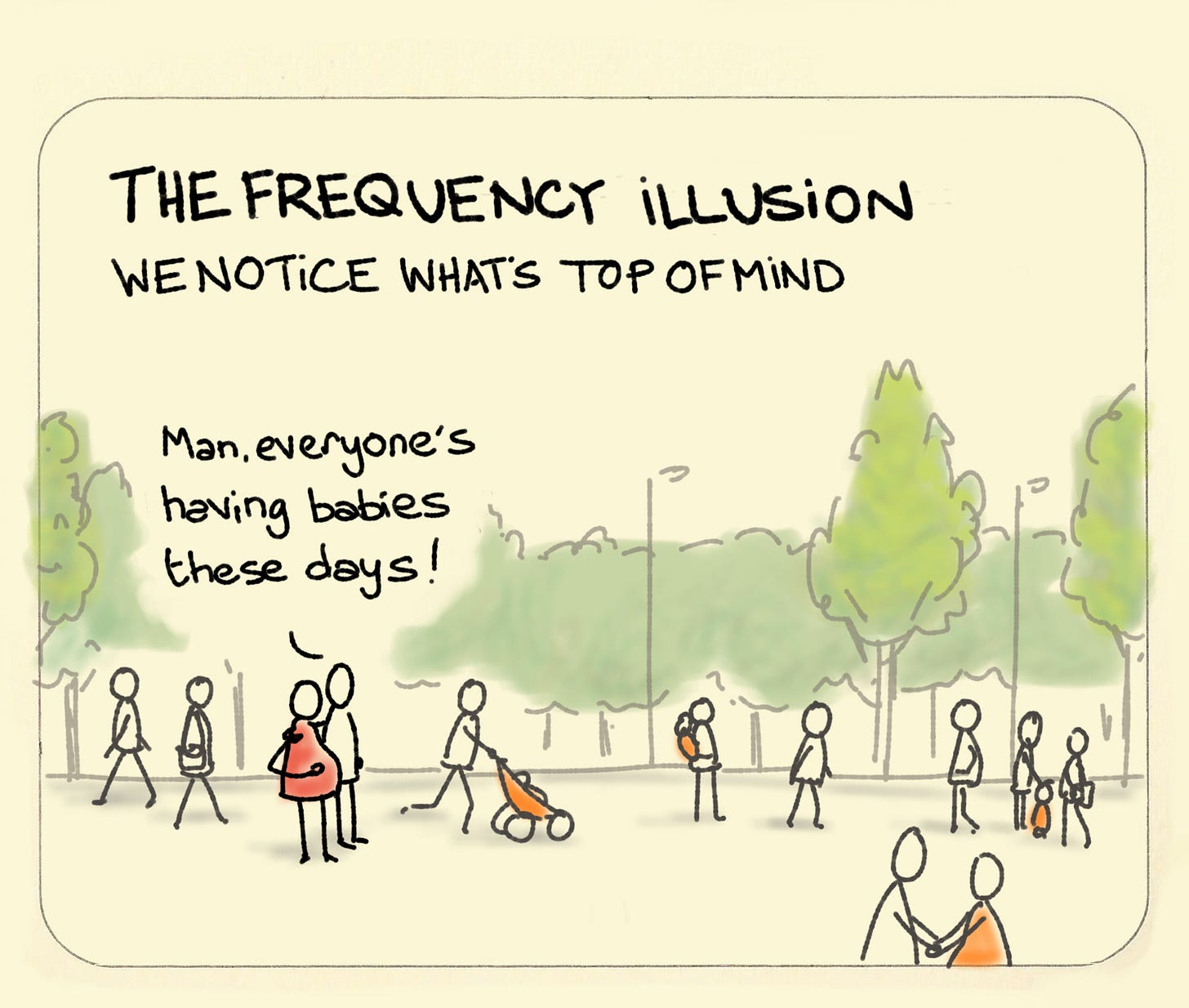

The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

In the 1970s and 80s, a far-left militant group from West Germany garnered worldwide notoriety for their bombings, kidnappings, raids of military supplies, and killings. They were often referred to by the founders’ names as the Baader-Meinhof Gang or as the Red Army Faction (RAF). One day in 1994, an American man called Terry Mullen mentioned the group to his friend — it had been years since he had last heard about them in US media. The next day, his friend called him up to tell him about an article he had just read in that day’s newspaper, referencing the Baader-Meinhof Gang. Following this, Mullen sent in a letter to a Minnesota newspaper, coining a new term:

“Within my circle of friends, the expression ‘Baader-Meinhof’ is now well known – as in: ‘I had the greatest Baader-Meinhof yesterday.’ It instantly communicates this complex and puzzling experience of seeing something in print so soon after learning about it.”

The phenomenon is now more commonly known as the Frequency Illusion. Our brains love finding patterns, so when we direct our selective attention towards something new, we are more likely to notice it than we were before.

What this means is that, to a good extent, the way we perceive the world is shaped by what we direct our attention to. As psychologist William James already found over a century ago: when our attention is directed by others, whether in the form of comments, algorithms, or notifications, we end up living lives that are “less our own”.

Our attention is fertile. At every moment, how we direct our attention allows for seeds to take root and grow. Staying soft and being ‘calm & fluffy’ is hard when you expose yourself and your attention to everything that bothers you. The world’s not all positive, of course, but it’s important to consider what you need to stay informed and to question why you need that.

It’s valuable to develop an intentional practice of directing your focus to what you want to see more of in the world. As Lao Tzu said over 2 millennia ago: your thoughts become your words, actions, habits, character, and destiny.

The digital landscape may be structured to favour conflict, but we retain the power to choose which seeds we plant and water. Our attention remains ours to direct. In that choice lies the difference between living lives dictated by external forces and cultivating gardens of our own design.

(- ‿- ) For your ears

Here’s an idea how you might want to direct your attention: spend more time with your friends. Check out this soul track with this exact title by the enigmatic singer and producer Pale Jay.

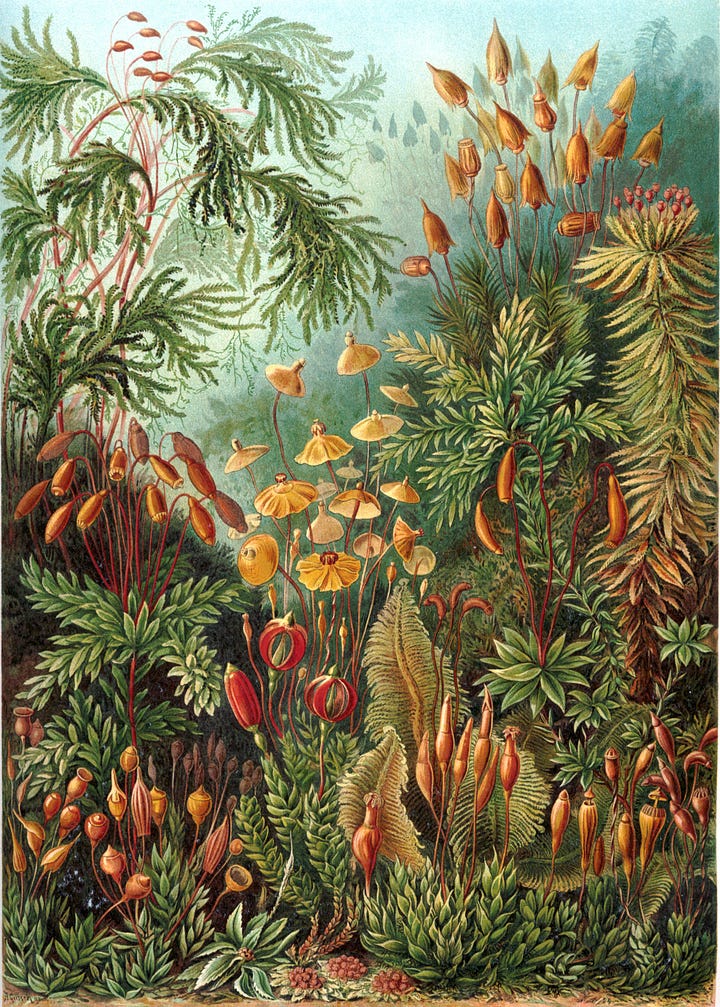

(◕‿◕✿) For your eyes

The level of artistry involved in zoological and biological sciences pre-photography has always been astonishing to me. Ernst Haeckel’s 19th-century drawings of flora and fauna are even said to have inspired the Art Nouveau movement. Since Haeckel passed away in 1919, his work is now in the public domain, and you can explore it in high resolution here.