Why people care about the environmental cost of AI, but not Trash TV

When it comes to ecological toll, why does AI get all the attention?

Why do we obsess over the carbon footprint of AI, but barely blink at the environmental cost of binge-watching trash TV? I’ve long been concerned about the environment and the impact of human activity on the world’s climate. I have made changes to my life because of it. Discussions about AI and its environmental impact have excited and perplexed me. It’s exciting that we address this as new technologies and consumption trends go mainstream. What baffles me is the odd selectivity about what we criticize.

Still reeling from the great Ghibli AI flood of 2025, last week, the internet found itself divided on people creating AI action figures of themselves. Some gleefully people generated the action figures through text prompts, while others derided the frivolous and inane activity as wasteful. And they’re not wrong. Image generation through AI is resource-intensive. So is training AI models. But why do we see these comments on posts that feature AI content, and not under photos of people eating meat, on a trip abroad, doing some hobby painting, or the latest clip from a trash TV episode?

I see 3 components to this:

Visible vs invisible consumption

Other issues with AI

Novelty

Visible vs invisible consumption

It’s obvious that so-called ‘Trash TV’ has a significant carbon footprint. TV shows like Love Is Blind fly participants and crew around. Telefilm, the Canadian government film agency, found that transport accounts for 58% of emissions of the creation of films & shows.¹ Then there’s all the equipment on set, generators, accommodation. All the episodes need to be edited, uploaded, and then distributed and streamed to hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of devices—episode after episode. And that’s just for one show.

Do we need trash TV? Do we need AI action figures?

I think that culturally, we treat trash TV as something that just happens. Trash TV has become a truth of life ever since Jerry Springer and Big Brother. We’re not responsible for making it. We just sit down, switch off our minds, and consume so that we have some drama to entertain ourselves with, gossip over with friends, and perhaps distract ourselves from the knowledge of our mortality.

Why is it so different for AI, then? For one, these uses of AI are much more visible. If someone spends 3 evenings per week streaming trash TV in ultra-HD on their 69-inch flat screen, nobody notices. But if they create an AI action figure of themselves and post it, the result of the inane action is there for the world to see and criticize.

The Ghibli and AI action figure trends may seem pointless. But they create easy avenues for people to experiment and familiarize themselves with a powerful new technology that is already changing the world. Is it a valuable use of energy to create action figure images using a model trained on other people’s creative work? No. Is it valuable to learn about what these technologies can do by trying them out? I’d argue yes.

That does not take away the moral obligation of corporations and governments to prevent the externalization of energy costs. Both trash TV and AI are being paid for through global wealth inequality and kicking the bucket down to our future generations like the boomers have been doing. That needs to stop, but that fight is not about AI or trash TV.

Other issues with AI

Another common trope seen across social media is that nobody wants, needs, or has asked for generative AI. While this is arguable, given OpenAI’s one billion weekly users, the sentiment reflects people’s unease and ethical concerns regarding AI. Many models are famously trained on data without authors’ consent. As technologists boast about the benefits of AI, they paint a picture of the future where a single AI agent can do the jobs of dozens of employees. They seem unsympathetic to the plights of people who are soon to be without a job or income. Meanwhile, the world outside of the Silicon Valley culture bubble has become exhausted and anxious from the relentless credo of “move fast and break things.”

For a recent example: One of the things AI is breaking is Wikipedia, with board member Maciej Artur Nadzikiewicz reporting infrastructure costs having “grown by 50% since January 2024 due to bots and AI scrapers.”

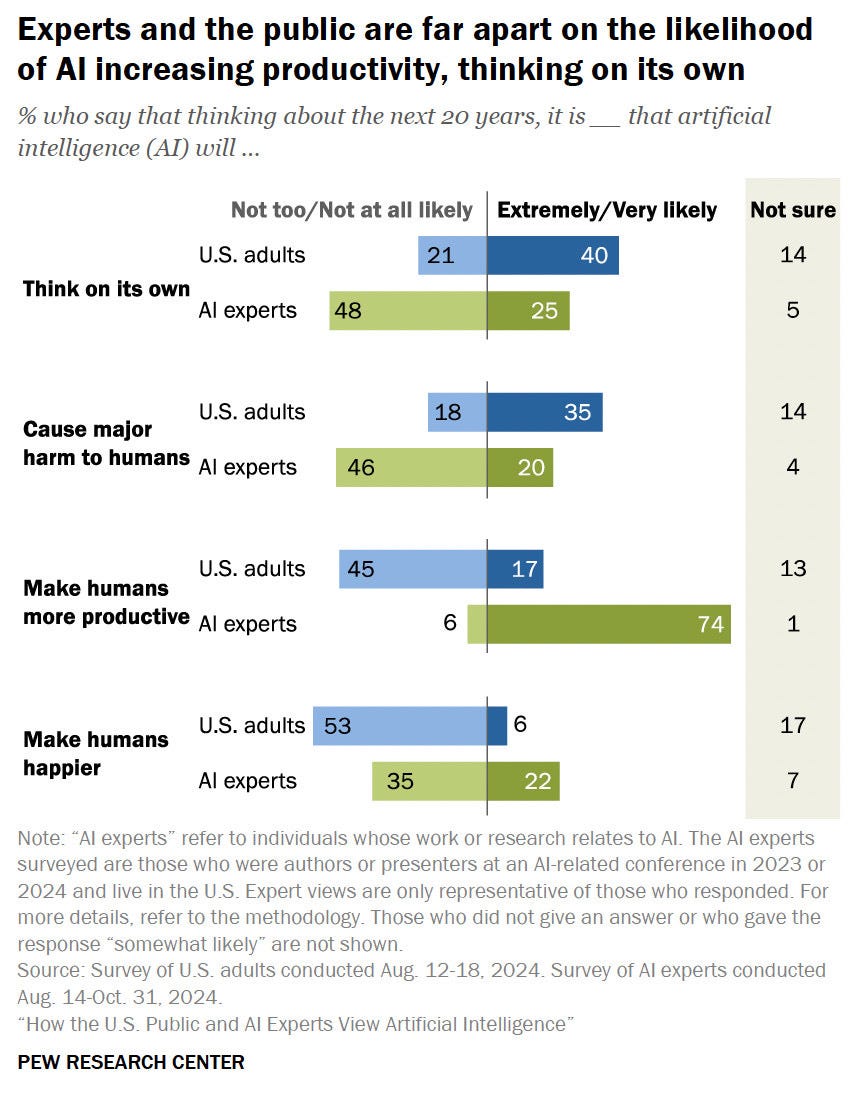

A recent report by Pew Research identified an ‘optimism gap’ regarding AI between experts and the general public. What I find especially interesting is that while the general public is skeptical about AI’s abilities, they’re actually more likely than experts to believe AI could think for itself and cause major harm to humans.

It is hard to formulate a clear response to the pace of progress other than expressing objections to the most apparent issues. In this case, the two that are easiest to articulate are that many of these models are trained on people’s data without their explicit (and often even implicit) consent, as well as the environmental cost. So it’s no wonder we hear these two objections, over and over. It is not all that people are trying to say, but it’s all that most can muster for the internet’s comment sections after an exhausting day of work and being datamined by tech giants.

It’s AI-nxiety (anx-AIty?) adding on to the general dread people already live with. This moment in our culture is underscored by the fact that one of the most viral songs right now is a bop by Doechii with the lyrics:

Anxiety, keep on tryin' me

I feel it quietly, tryna silence me, yeah

Anxiety, shake it off of me

Somebody's watchin' me, it's my anxiety, yeah

If you’ve not heard it: kudos to you. Many people envy your social media habits.

Novelty

Lastly, the fact that generative AI is a relatively new mainstream phenomenon makes people feel like their critique can have an impact. We also don’t yet have much language around AI as part of our culture. For the accelerated meme generation of social media, we have phrases like ‘brain rot’, ‘echo chambers’, ‘doomscrolling’ and ‘FOMO’. For dramatic reality tv, we have ‘trash TV’, ‘binge-watching’ and being a ‘couch potato’. For TV and social media, all the criticism, all the unease, all the objectionable qualities have been reduced to one or two-word quips. AI, too, needs to be critiqued, and it needs language to critique it with.

AI is a “before and after” type of technology, just like there was a world before and after the nuclear bomb, the world wide web, or the smartphone. Like it or not, it is here, and it seems unlikely that we’ll go back to the “before” world. So, by all means, develop your moral framework so you can clearly articulate how AI fits into it. However, do yourself a favour and gain some familiarity with the technology by playing around with it on regular occassion, because this technology advances quickly.

Don’t let tomorrow take you by surprise.

Footnote

¹ Telefilm Canada. (2024). Estimating the carbon footprint of Canada’s audio-visual sector. https://telefilm.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/EstimatingCarbonFootprint-EN-GSG.pdf

(- ‿- ) For your ears

I’ve been exploring this new album by accordionist and multi-instrumentalist Walt McClements. Pitchfork gives it 8/10 and describes it:

“The more I’ve heard it, the more I’ve understood that it does what so much of my favorite art does—hands me something to carry into the world, to make my load and hopefully someone else’s a little more tolerable.”

(◕‿◕✿) For your eyes

Argentinian street artist and illustrator Federico Calandria’s work comments on our relationship with nature and technology.