The slow streaming movement: counteracting Spotify & co's economic impact on artists

A better way to distribute your attention (and money) to the artists you love

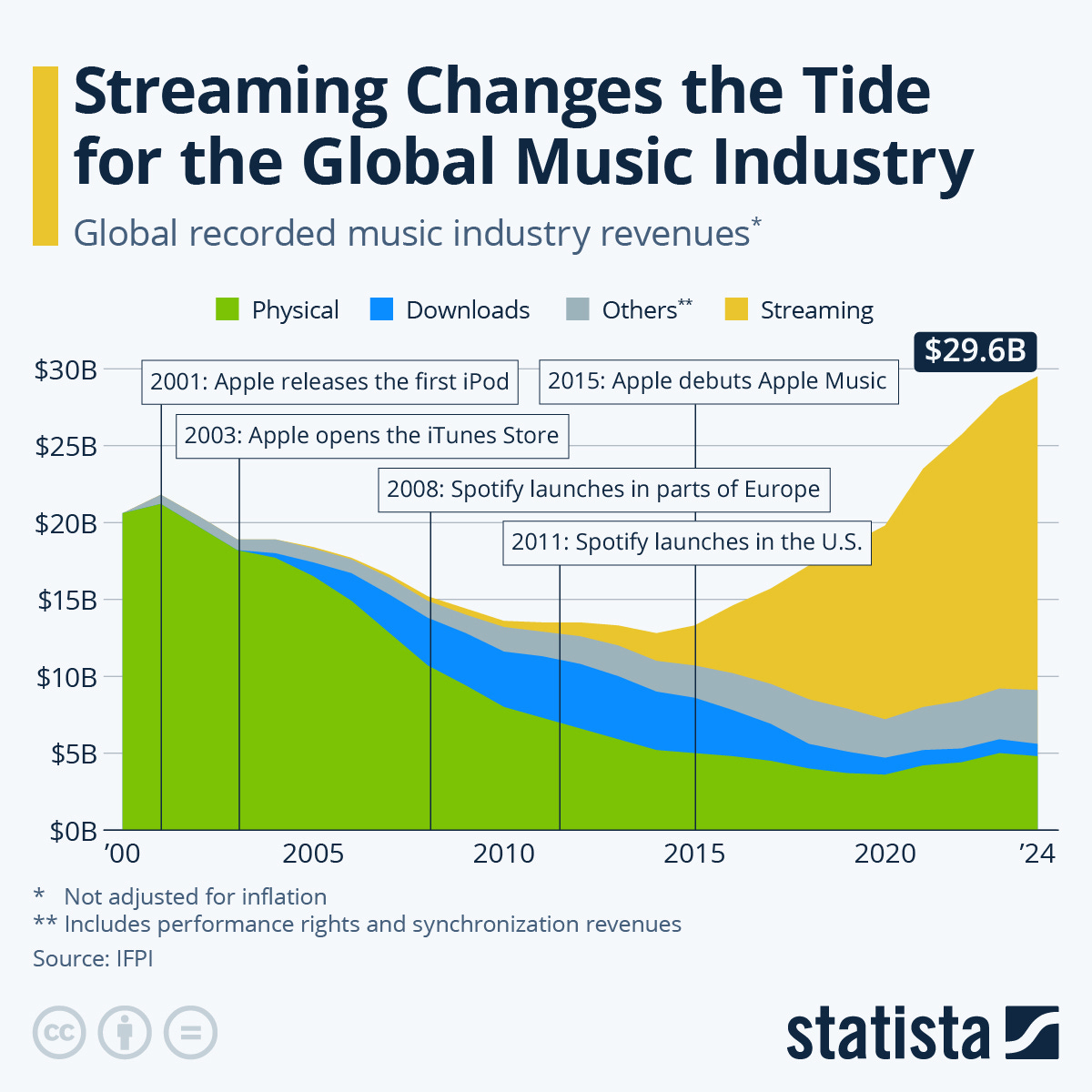

You have probably seen posts from artists and music lovers complaining that Spotify is not paying artists enough. Despite being the largest music streaming service, the biggest contributor of revenues to the recorded music business, and the most successful at getting millions of people to pay a monthly subscription fee, its ‘per-stream’ royalty rate is relatively low. Why? And what role does the average listener have in it?

The primary reason why Spotify’s royalties are so low is, because it is extraordinarily good at getting people to listen to music. This dilutes the payout per stream. When people pay money for their subscriptions, that money gets pooled together. All streams they make also get pooled, the money gets split over those streams, and payouts are made. If you collectively paid $1000 in subscription fees and listened to 1000 different songs just once, $1 will go to each song. If one service has 100k streams and the other just 10k, but the same amount of money is collected, then the per-stream rate will be lower for the service with a higher amount of streams.

Why Spotify wants you to listen more

Why is it a good thing that people listen to more music on Spotify? To build a sustainable music streaming service, Spotify must ensure people subscribe and stay subscribed. One of the reasons why people unsubscribe from services is a lack of utility. This can be for many reasons: the music they’re looking for isn’t available, they struggle with the interface, or they just don’t end up listening enough to warrant the $12 a month. This has created a reality where Spotify and other streaming services try to find ways to insert music into every aspect of your life. Spotify’s marketing campaigns have donned slogans like Soundtrack Your Life and Music For Every Moment. The more time you spend listening to music in the app, the less likely you are to unsubscribe. In other words, the more you use the app and the longer your sessions are, the more likely you are to keep paying your subscription fees.

To keep people subscribed, Spotify must maximise engagement. It does this by meticulously optimising playlists and personalised music recommendation algorithms. Spotify isn’t alone in that, but it has had by far the most success: it’s responsible for 32% of the world’s 818 million music streaming subscribers. The second biggest, Tencent Music, comes in at less than half of that. Spotify’s 32% is as much as Apple, Amazon & YouTube’s combined music streaming subscriber market share.

Managing costs I: Ghost artists

These playlists and algorithms are also 2 of the streaming service’s most important tools in driving down its licensed music costs. Spotify’s mood playlists are alleged to contain music from ‘ghost artists’. It’s said that producers get ‘bought out’ for these songs, so they only get paid a flat fee once, after which the music is released under an alias by a company. These tracks then get paid at a lower royalty rate than your typical track. Instead of splitting the $1000 from the earlier example over all tracks, it gets more complicated. Let’s say half of the plays in a certain period are discounted at 50%, so instead of $500 being split over them, only $250 would be split. This means for that period, only $750 gets divided and paid out rather than $1000.

I must make a note here to say two things: in reality, these savings on Spotify’s end are likely much more marginal than the 25% in the example. Secondly, the math is a lot more complex, and the above is a vast oversimplification. If you’d like to develop a deeper understanding of this, I suggest picking up the book Mood Machine by Liz Pelly, which dives much deeper into this topic.

Managing costs II: The algorithm

Before we move on, there is one more topic to address: The Algorithm. Spotify’s various radio modes are an important driver of streams and thus strongly influence the way streams are generated and royalties get distributed. To make it more likely for one’s music to appear in these recommendation algorithms, one can enter it into ‘Discovery Mode’. In exchange for a discounted royalty rate, similar to those for ghosts artists mentioned before, you make it more likely that your track gets recommended. A way to advertise your music without having to pay upfront, says Spotify. The contemporary equivalent of payola, argues Pelly’s book.

Spotify is in a tough spot. It can’t operate its music streaming service as a loss leader, like Apple, Amazon, or Google with YouTube Music can do. Thus, it faces more economic pressure to drive down its costs to make its business sustainable. I’m not saying this in defence of Spotify; I’m merely pointing out that the economic game that streaming services all play is the same, so switching from one to another isn’t the impactful move many think it is. Paying $10 to a different service doesn’t magically create more money because all streaming services pool money together and split it over the total streams. The reason some music streaming services’ royalty rates are higher is mostly because people listen to less music there (which is also why they have fewer subscribers).

With advances in generative AI, it also doesn’t take much imagination to see the next looming crisis: what if music streaming services start generating music directly personalized for their users? How will that compete for attention versus licensed music? It’s possible that it could extend passive listeners’ sessions beyond traditional recorded music, because it doesn’t have to deal with the constraints of each song being fixed in arrangement, instrumentation, energy, length, etc. How will the revenue be split then?

So, besides spending more money on music—a highly impactful way to support your favourite artists—you can change the way you listen to music on streaming services, by opting out of algorithms and bringing more intention to your selection.

How to be a better streaming music consumer

In the introduction—yes, the music business can be complex, hence the 10-paragraph intro—we established these 3 points:

Streams get pooled together, and the subscription money gets distributed over these streams.

The proportion of distributed money can be decreased through lower-royalty tracks by ‘ghost artists’ in playlists and through discounted tracks in algorithmic recommendations like radio modes.

Advances in AI will further complicate this.

What does ‘better’ mean?

Many people are concerned and confused about the ethics of music streaming. So, let’s take ethics as the guiding principle for ‘better’ streaming. Streaming as a system has helped the recording industry recover from the piracy heydays. There are economic issues in that system, from the contracts between artists and the industry to the licensing agreements with streaming services, which need to be battled out in the industry.

Some people suggest switching to streaming services that have a different model for how they pool money or that have higher royalty rates. You can do that. In my opinion, that doesn’t solve the problem because the economic underpinnings aren’t addressed properly through that. Others suggest buying more music, seeing more shows, getting more merch, etc. Yes, yes, yes. Do all those things. You can even get actively involved in addressing these issues, for example through Subvert, a cooperative which has set out to build an artist-owned Bandcamp. (disclosure: I’m a founding supporter member)

The main question I want to answer here is: as someone who streams, what can you do better? What new habits can you develop? How can you counteract the forces of the economic underpinnings of the music streaming system?

Your streaming goals

Let’s establish the goals for ‘better’ music streaming:

Direct more value to the artists you believe in.

This can be achieved by ensuring they have a higher listening % of your total streaming share.

Avoid contributing to mechanisms that devalue music.

Reshape your impact on the streaming economy.

Stream albums

Genre playlists are great for music discovery, but if you rely on them too much, you let the curatorial policy decide where your money and attention goes. You can use them to discover artists, but then go check out an album or two by that artist.

Collect the albums. Build a collection. If you don’t know what to listen to—instead of going to a radio feature or a personalized playlist—hop into your album collection.

Slow down your listening. Instead of letting the algorithm drive your mood and music selection, do it yourself. The reward is that you’ll develop deeper connections to the music you love, as you’ll listen to it in a larger variety of settings, moods, seasons, etc.

Curate your own playlists

Streaming services’ official playlists are strategically used to manipulate listening behaviour to manage costs and to get people to stay subscribed. These playlists are prioritized in search features, so you’re more likely to land on them than user-generated playlists (this dates back a decade). Streaming services have an incentive to decide what you listen to. Create your own collection with intention, so you know that your attention and streams go towards artists you want to support.

Stay up to date with independent curators

It can be hard to figure out what to listen to without the help of algorithms, but curators still exist if you look for them. One of my trusted sources for curation is Michail aka Opium Hum who runs a channel called Hyper Real via his Instagram and on Telegram.

Another curator I enjoy is The Slow Music Movement—a YouTube channel full of excellent recommendations. And of course I can highly recommend the work my former colleagues at COLORS do to bring artists to their global stage.

I’m always looking for more trusted voices, so please drop your favourite curators in the comments by clicking the button at the bottom.

Ask your friends

You can ask your friends about what they’re listening to. Or discover music through their IG stories or other social media. Personalization algorithms have made daily music listening a lonesome experience. These personalized algorithms ensure that every person will always find something to listen to, but that tears away at the shared experience of music. Restoring that shared experience is as easy as asking a question.

Here’s a recent discovery I made: Ghanaian ‘Burger Highlife’ record Seaman Jolly by Paa Jude. My favourite track is Odo Refre Wo.

Be intentional & gentle

The best way to counteract the economic forces that steer your music listening is by bringing more intention to who and what you listen to. You don’t have to take this all the way. It’s ok to make use of the conveniences offered by these services. But when you can, bring a little more intention into it.

Your favourite music deserves your attention.

Footnotes:

This article is explicitly not about how to solve the industry’s woes. I’ve spent 15 years writing about that and about half of that leading product at niche music streaming services experimenting with alternative economic underpinnings. For a dedicated newsletter that looks at this more from an industry perspective, I highly recommend

, a newsletter I founded in 2016, now run by Walraven.There are streaming services that pool money & streams together per user. This may lead to higher payouts for the artists you listen to, but it doesn’t increase overall payouts, and it’s questionable whether it leads to significant changes in the distribution of royalties.

The most impactful thing you can do for musicians is to spend more money on music.

One detail. Spotify doesn’t care if you actually listen to the music. To them, mindless streams are just the same, or even better.

im super excited for this new artist I found!

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DIPOJjXySwj/?igsh=NTc4MTIwNjQ2YQ==